Peril-Sensitive Sunglasses?

How outdated paradigms prevent us from seeing the world as it is.

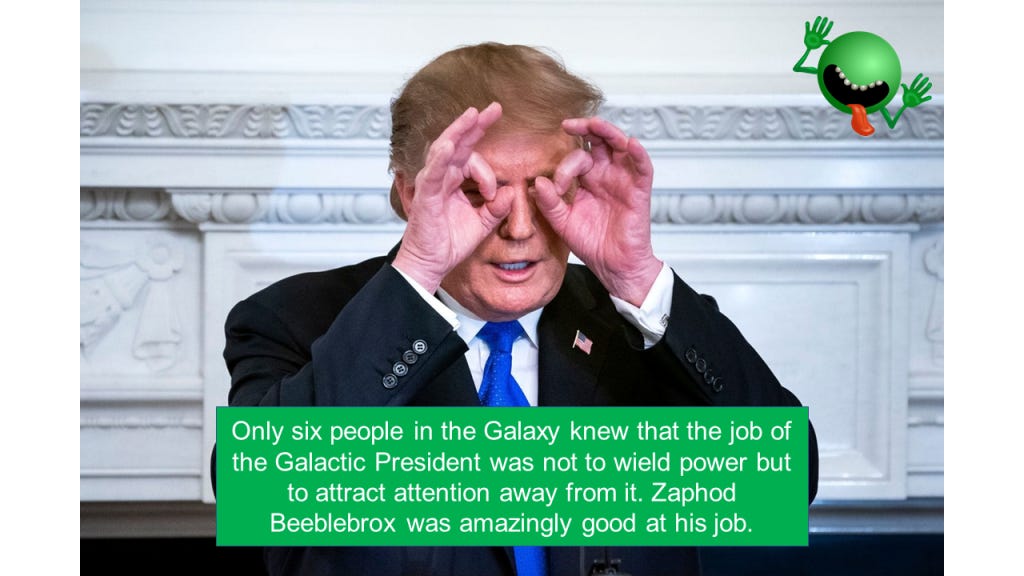

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is an underappreciated book. Apart from being funny and inventive – forever establishing the number 42 as the answer to everything – it is also prophetic. Few people realize that Douglas Adams predicted Donald Trump when inventing the President of the Galaxy Zaphod Beeblebrox.

Among the many insane inventions from Mr. Adams’ five-part trilogy, the peril-sensitive sunglasses stand out. They are designed to keep the wearer relaxed by blocking out any signs of danger and are an almost perfect metaphor for the society we live in today.

They were a double pair of Joo Janta 200 Super-Chromatic Peril Sensitive Sunglasses, which had been specially designed to help people develop a relaxed attitude to danger. At the first hint of trouble, they turn totally black and thus prevent you from seeing anything that might alarm you.

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

Increasingly, our world seems governed by people oblivious to the dangers of climate change and ecological destruction. A cynic could argue that this is a natural development: given the magnitude of the challenges facing humanity, only opportunists and crooks run for political office. To them, political power is about getting rich and reserving a seat in the lifeboats. Decent people, on the other hand, find running for political office about as appealing as being appointed the captain of the Titanic.

Even though there are many indications that the cynics are right, I refuse to believe that all the people meeting at the WEF in Davos are evil. Most of them – like Bill Gates – seem genuinely convinced that the paradigm of free-market capitalism can solve all our problems. They have replaced the belief in an invisible God with an equally solid but irrational belief in the invisible hand of the market. As I will discuss in an upcoming post, capital income is a faith-based concept without any rational justification. However, the idea is powerful enough to justify the erection of temples built out of marble.

Otto von Bismarck once observed that it is wrong to assume that everyone who disagrees with us is either evil or stupid. Reality is not a Disney movie with clearly defined good and evil and a guaranteed happy ending. Instead, we must come to terms with the fact that different groups of perfectly decent, respectable, intelligent, and well-educated people have opposing views on how to deal with the climate crisis. This is not new in human history, but it is still somewhat annoying because it was not supposed to happen in an enlightened society.

My take on the story is that both the Scientific Revolution and The Enlightenment have been misrepresented. Our society never developed a profound appreciation for science, and there are few indications that people are more rational today than in the Dark Ages. Science succeeded because it was useful! However, the fact that people like vaccines, the internet, and smartphones, does not imply that they understand and appreciate the scientific method. On the contrary, we now routinely use technologies without having the slightest idea of how they work. For all we care, they might as well have been a gift from the Gods.

I just reread Thomas Kuhn’s “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” and the analysis below borrows heavily from his book. Accordingly, every human has a worldview consisting of a set of paradigms we use to interpret the world. Since we want our paradigms to be “true,” we invest significant mental effort in looking for facts that validate them. This is often referred to as confirmation bias; nobody actively seeks information that will invalidate their worldview. The expression cognitive dissonance describes what happens when people are confronted with facts contradicting their accepted paradigms.

Note that this behavior has nothing to do with intelligence or level of education. Ordinary science, to borrow another expression from Mr. Kuhn’s book, is the systematic endeavor to validate paradigms. Scientists perform experiments because they believe that they know the outcome, which is why so many important discoveries happen by accident. We often learn more from failed experiments than from successful ones.

Max Planck famously pointed out that science does not progress because professors change their minds but because old professors die and are replaced by new ones. If we think of the brain as a neural network, we can see the truth in this statement: it is easier to train a fresh brain than to retrain an old one. Once specific cultural thinking patterns have been established, it is very difficult to change them. Jeremy Lent has also made this point in The Patterning Instinct.

The consequences of these insights are profound. First, we realize that there is truth to the statement that “people are born ignorant, but not stupid. Stupidity requires an education” (Russell, History of Western Philosophy). It is possible to fill a brain with so much irrelevant information that it loses its ability to function. Authoritarian regimes and religious organizations understood this long ago. If you force children to memorize religious or political texts, they will have little capacity left for independent thought. Conversely, good education should strive to keep the neural network agile rather than simply filling the brain with facts. I am fascinated by how different people seem to be in this respect. Whereas some people retain an agile brain to an advanced age (Noam Chomsky being the prime example), others seem to be locked in already in their 20s. Neurologists should probably investigate this if they have not done so already.

We need to accept that the people disagreeing with us are neither stupid nor evil. They understand the world too, but their understanding is based on a different paradigm. In the 14th century, the Catholic Church appointed a panel of experts to decide whether the visions experienced by Birgitta of Sweden were from God (Oppenheimer et al., Discerning Experts). By all accounts, they took their job seriously. Likewise, a medieval doctor had no problems explaining the causes of illness. He just struggled to provide a cure.

This also explains why the internet and social networks have been bad for political discourse. Not only do they saturate our stone-age brains with irrelevant information, but the search algorithms have been carefully designed to deliver confirmation bias on steroids. On the internet, everyone is provided with a personalized reality.

When people first became aware of anthropogenic climate change in the 1970s, they obviously began to look for solutions within the existing paradigm of science, technology, and capital (the STC paradigm): we solve all problems through investments in science and technology. There is absolutely nothing wrong with believing in science. However, the belief that science can solve all problems is unscientific. No matter how much money we invest, we will not be able to invent the perpetual motion machine or travel faster than the velocity of light.

When the study Limits to Growth was published in 1972, the global population was 3.8 bn, the carbon concentration was 330 ppm, and human energy demand was at 225 EJ (exajoule). Today, the population has increased by 110%, the carbon concentration by 28% to 420 ppm, and energy demand by 160%. Consequently, we are now in the midst of the Sixth Extinction under climatic conditions unprecedented in human history. And things are deteriorating fast; humanity is driving off a cliff just like the oil companies predicted we would in the 1970s.

Why did the world not respond to the threat in 1972? Because the warnings were in stark contradiction with the existing worldview of a world constantly getting healthier and wealthier through science, technology, and economic growth. Any evidence to the contrary was ignored. The cognitive dissonance was resolved by putting on peril-sensitive sunglasses and ignoring the obvious. Note that hoping for technology to solve our problems is deeply irrational. This is why I find the statement by Bill Gates that “we need an energy miracle to prevent catastrophic climate change” so remarkable. You know that you have a problem when the Pope demands action and Bill Gates hopes for divine intervention. The sentence “we need a miracle” should only be used as a joke or an expression of despair in a rational society.

The climate crisis is thus also a crisis of science, technology, and capitalism. Even though an increasing number of people realize that the old paradigms are useless, far too many people are stuck in the old way of thinking. How can we change this? Again, Kuhn offers several important insights:

People are not prepared to change their paradigms unless there is a crisis. It must be abundantly clear that the old paradigms do not work anymore.

A new and better paradigm must be available, as people cannot live without a worldview.

Individuals are not always able to change their paradigms. There will always be people who will refuse to change their minds until the end of their days.

Therefore, paradigm change is a societal process that takes time.

The classic example of a paradigm change was the switch from the Ptolemean to the Copernican worldview in the 16th century. Compared to the climate crisis, it had several advantages. First, it had little impact on everyday life, meaning that only a small group of people needed to change their minds. Second, the discovery was immediately valuable as it led to better astronomy, navigation, and technology. It is no coincidence that the scientific revolution coincided with the European expansion and colonization of the world, as navigation and mapmaking required modern astronomy. Furthermore, the combination of calculus with Newtonian mechanics revolutionized technology. Both subjects have been taught to engineering students for the last 300 years with only minor modifications. And third, even though the Catholic Church tried to prevent scientific progress, there were enough influential people who wanted to break the power of the church. Most of the scientific hotspots in the 17th century were in protestant countries, beyond the reach of the Holy Inquisition.

Unfortunately, things are not so easy today. The magnitude of the challenge can be understood easily:

Getting rid of fossil fuels will have a massive impact on everyday life, meaning we need to convince billions of people of the need for a new paradigm.

The discovery that greenhouse gases destroy the atmosphere is not useful. It will always be easier to emit exhaust gases into the atmosphere than to capture or clean them.

Fossil fuels are cheap and practical. Since technology and innovation will hardly make them more expensive, governments need to step in with legislation.

All countries depend on fossil fuels, and greenhouse gases cannot be stopped at the border. Nations, or blocks of nations, that implement strong restrictions on greenhouse gas emissions will experience higher costs while still suffering the same consequences from climate change as the others. Therefore, they are more likely to invest in climate adaptation than mitigation.

There is no generally accepted alternative to growth and technological progress. Socialism is an alternative to capitalism but still requires economic growth. Other options, such as Degrowth or Doughnut Economics, are exciting ideas for new paradigms but are far from generally accepted in mainstream politics.

Oil is still the elixir of power that is needed to power armies.

So how do we get out of this mess? Since it is unlikely that a paradigm change will happen fast enough to prevent Climate Armageddon, we must narrow down the discussion to a small number of ideas that are acceptable to as many people as possible:

We need to stop the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from increasing. If we fail, human civilization is doomed.

There is no guarantee that fanciful technologies like carbon capture or geoengineering will ever work. Thus, we need to phase out the extraction of fossil fuels as soon as possible. Curiously enough, the Paris Agreement forgets to mention this.

There is no agreement on how fast this can happen or the societal impact. Thus, it is pointless to define emission targets. A much better alternative is to implement a global carbon tax and increase it gradually until it has the desired effect.

For such a tax to work, it must be enforceable and coupled with a redistribution scheme to ensure Climate Justice.

The system must encourage peace and international collaboration.

This is the idea behind Global Climate Compensation. I have a strong feeling that a vast majority of the world’s population agrees on these points.

Think of paradigms as Venn diagrams. Whereas few people agree on everything (the intersection of all paradigms), most people share some common beliefs. I am not interested in the political views, sexual orientation, or religious beliefs of the electrician who recently installed my solar panels. However, we agreed that I would pay him accordingly if he did a good job. I have negotiated contracts with companies in Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, the USA, Russia, Brazil, and Japan during my professional life. The cultures are different, but we always succeeded because we focused on the essentials.

The plot below showing the carbon dioxide concentration of the atmosphere says it all. While we were talking, discussing, and arguing, the CO2 concentration was rising faster and faster. We will soon hit the point of no return.

To borrow from an Honest Government Ad: If humanity wants to continue with its favorite pastime, i.e., continuing to live on this planet, we need to act fast and focus on the main issue: rapidly reducing fossil fuel extraction. GCC accomplishes this by invalidating any business model dependent on fossil fuels. If we fail to do so, we will need a lot of peril-sensitive sunglasses. And don’t forget to bring your towel.

Fantastic post Henrik.

But how do we get the movement and the numbers to support the change?

The Marketing Division of the Sirius Cybernetics Corporation has a seemingly infinite candidate pool. We know their fate.